It was 49 years ago Thursday when an Army officer in Houston summoned Muhammad Ali three times to step forward for induction into military service during the Vietnam War, and the heavyweight world champion refused each request.

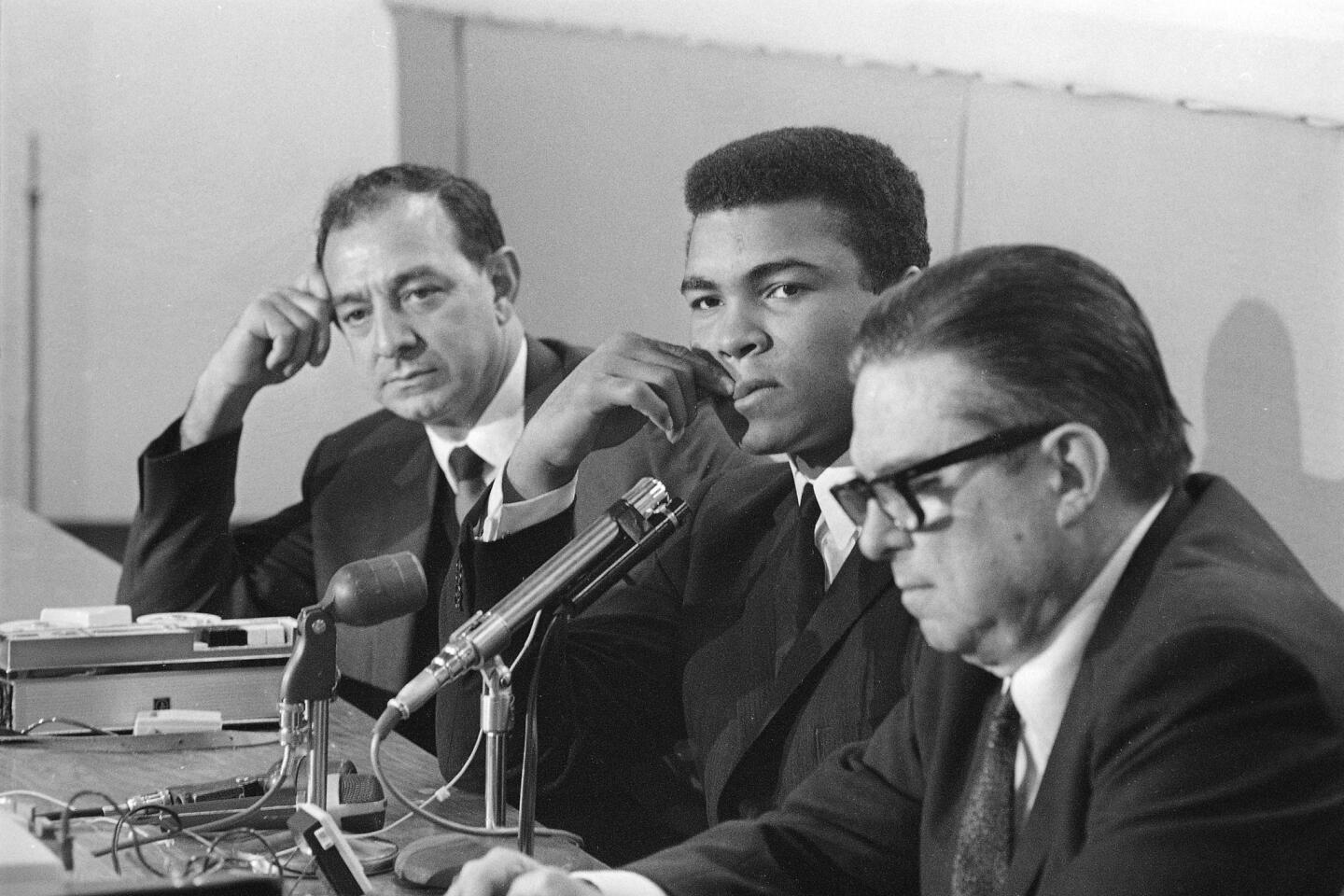

“Looking back on this requires you to immerse yourself back in the time. At the time he made the decision, nobody had gone against a U.S. war – 99% of the public were for the war,” said veteran fight promoter Bob Arum, who helped broker a deal one year earlier that allowed Ali to skirt a ban in Chicago and fight George Chuvalo in Toronto.

Originally, in 1964, Ali didn’t qualify for draft eligibility, but when standards were lowered by 1966, he did. Ali famously told reporters that year, “I ain’t got nothing against them Viet Cong,” and he was influenced by his mentor, Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam, who had conscientiously objected to World War II.

“Ali thought if it was good enough for Elijah, it was good enough for him,” said Jerry Izenberg, the longtime sports reporter for the Newark Star-Ledger who covered Ali’s entire career. “It was very simple: Go to jail or betray what he believed in. Very simple at the time … but it became very complex.”

Ali’s refusal to step forward in Houston saw him stripped of his boxing license and World Boxing Assn. title, and it stopped him from traveling abroad for the multiple fights he was offered

Both the State Department and FBI labeled him a flight risk after an all-white Texas jury convicted him of felony refusal to be drafted in June 1967.

As appeals were made to keep him out of jail, and the fighter rejected overtures for a compromise to enlist, the stripped champion at his peak was kept out of the ring from March 22, 1967, until Oct. 26, 1970.

It didn’t matter that an appointed examiner, Lawrence Grauman, had previously met with Ali privately and concluded that his objection was sincere. That was strangely overruled by an FBI probe.

And it didn’t matter that attorney Arthur Krim, the head of United Artists and the Democratic Party treasurer, met with President Lyndon Johnson to secure a proposed military service arrangement preferential to Ali.

“Ali wouldn’t even have to put his uniform on,” said Arum, who worked in Krim’s firm. “He’d just give a couple [boxing] exhibitions at a couple military bases and would be able to continue fighting as a professional. Ali, after a famous meeting with a lot of black athletes, including Jim Brown, turned it down. He wasn’t afraid of combat. There was no chance he would be in combat. His decision was completely principled. He gave up a lot by doing it.”

Izenberg said he learned the depth of Ali’s resolve while visiting the fighter at a gym in Toronto days before the Chuvalo fight in March 1966.

“Ali’s on his stomach on top of a training table when I walk in,” Izenberg said, “and I told him, ‘I’m going to tell you the truth, this is what I’m hearing, and you may not like it, but a lot of young men who are against the war are coming to Canada and getting sanctuary. A lot of them don’t want to fight, so I’m interested in if you’re going to come home?’

“He jumped off that table and got in my face and said, ‘You, of all people, should know! How can you say that? America is my birthplace, and nobody is going to chase me out of my birthplace! I’ll go to jail. I’ll go back. I’m going home. I don’t make the laws or the rules, but if the law or rules are that I have to go to jail, then I’m going to go to jail.’ That’s the first time I really believed.”

Izenberg returned home and began writing columns supportive of Ali’s position, the first headlined, “With Liberty and Justice For All.”

He recalls not too long after seeing a man smashing out his car windows with a sledgehammer.

After Ali’s final bout (a knockout of Zora Folley at Madison Square Garden) before the Houston showdown, he summoned a small group of reporters, including Izenberg, to his hotel room in Manhattan.

“Fellas,” he said, “I’m not thinking about the next fight. I’ve got a bigger fight coming up…. If I go into Vietnam, killing people, if I thought that would benefit the 19 million blacks in this country, I’d go and you wouldn’t even have to tell me. But it’s not my war, and it’s against my religion to go to war, so I ain’t going, and in the next few weeks you’re going to be writing more about me than you ever did.”

Izenberg monitored Ali during the hiatus, staffing some of his speeches on college campuses, his work on a Broadway musical, “Buck White,” and his diminished lifestyle, recalling how he loaned the champion-turned-pariah $20 to get home one night.

They bonded over their mutual admiration of James Earl Jones’ Broadway portrayal of former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, specifically a line in “The Great White Hope” about the boxer’s disdain for the trappings of his championship belt.

And Izenberg was moved by Ali speaking at a New Jersey college, hearing a young black man from the balcony tell Ali, “I’ll go in the Army for you for $1,000.” Ali answered, “No, brother, your life is worth a lot more than $1,000.”

Said Arum: “The truth is he didn’t really mean it as a statement for everyone against the Vietnam War, but for the black people who were treated badly by the government.… What did the Viet Cong do to them? How the blacks had been treated here – the segregation in the restrooms, they couldn’t eat in diners, couldn’t stay in hotels. Why should I fight for this country when they’ve treated me this way?”

With his case bound for the Supreme Court in early 1971, favorable state rulings in 1970 allowed Ali to fight again -- first in Georgia, then New York.

Then-Georgia Gov. Lester Maddox, who was pro-segregation, conducted an interview with Izenberg before Ali’s comeback bout, a technical knockout of Jerry Quarry in Atlanta, and said: “It’s a sad and tragic day when a man who will not fight for his country will get in the ring and fight for dollars. So I have proclaimed tomorrow night a night of mourning for patriotism in the state of Georgia.”

After the Supreme Court ultimately freed Ali, he fought Joe Frazier on March 8, 1971, in what was considered the biggest sporting event of the century. A bitterly divided nation looked on as the establishment’s Frazier met the antagonist Ali.

Frazier won by unanimous decision, knocking Ali down late in the bout.

But Ali responded with two triumphs over Frazier. In between those victories, he recaptured the WBA heavyweight title with his legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” knockout of previously unbeaten George Foreman in Africa in 1974.

Izenberg, now living in Henderson, Nev., hasn’t visited Ali in three years. He has been left too upset seeing the former champion ravaged by the effects of Parkinson’s disease. Ali’s 75th birthday is on Jan. 17.

“I know how I’ll always remember him,” Izenberg said. “After he beats Foreman, there’s a horrible rainstorm. Dave Anderson [of the New York Times] and someone else was with me. We say, ‘Let’s go look for him.’ The fight was at 4 in the morning. Now it’s like sunrise, like 7:30, we’re going to look for him, and I say, ‘With all of his [girls], he’ll be down by the river.’

“We go down by the Congo River and damn if he’s not there, facing across the river to the French Congo. He’s got his back to us. For once, we keep our mouth shut. Too good a moment to spoil.

“He’s staring and staring. Seemed like it was 20 minutes, but it was probably two or three. God knows what he’s thinking?

“All we’ve got is his back. Before he turns around, he throws his arms up in the air, like a ‘Rocky’ pose. Stands there for like a minute or two. Turns around, starts walking back toward us, sees us, waves.

“He gets real close and says, ‘Fellas, you’ll never know what tonight meant to me.’”

Izenberg captured the climactic scene in a story, ending it by writing, “In that moment, he was indeed the king of the world.”

-1737949691-q80.webp)

-1739158788-q80.webp)