When Muhammad Ali dies, a light will go out in this world and it will be the brightest light that I have known in my lifetime.

Conflicting reports about Ali’s health are coming out of America.

Some of his loved ones are optimistic, like his daughter May May, who posted a picture of Ali watching the Super Bowl on Sunday night and claims that he is fine.

But his brother Rahman insists the great man is no longer able to speak and is nearing the end of his life.

“It could be months, it could be days,” said Rahman. “He’s in God’s hands.”

For those of us who have watched and loved Ali all of our lives, it is impossible not to contemplate his end with shock and sadness.

Muhammad Ali has fought Parkinson’s disease for almost 30 years. It is one fight that, in the end, he will not win.

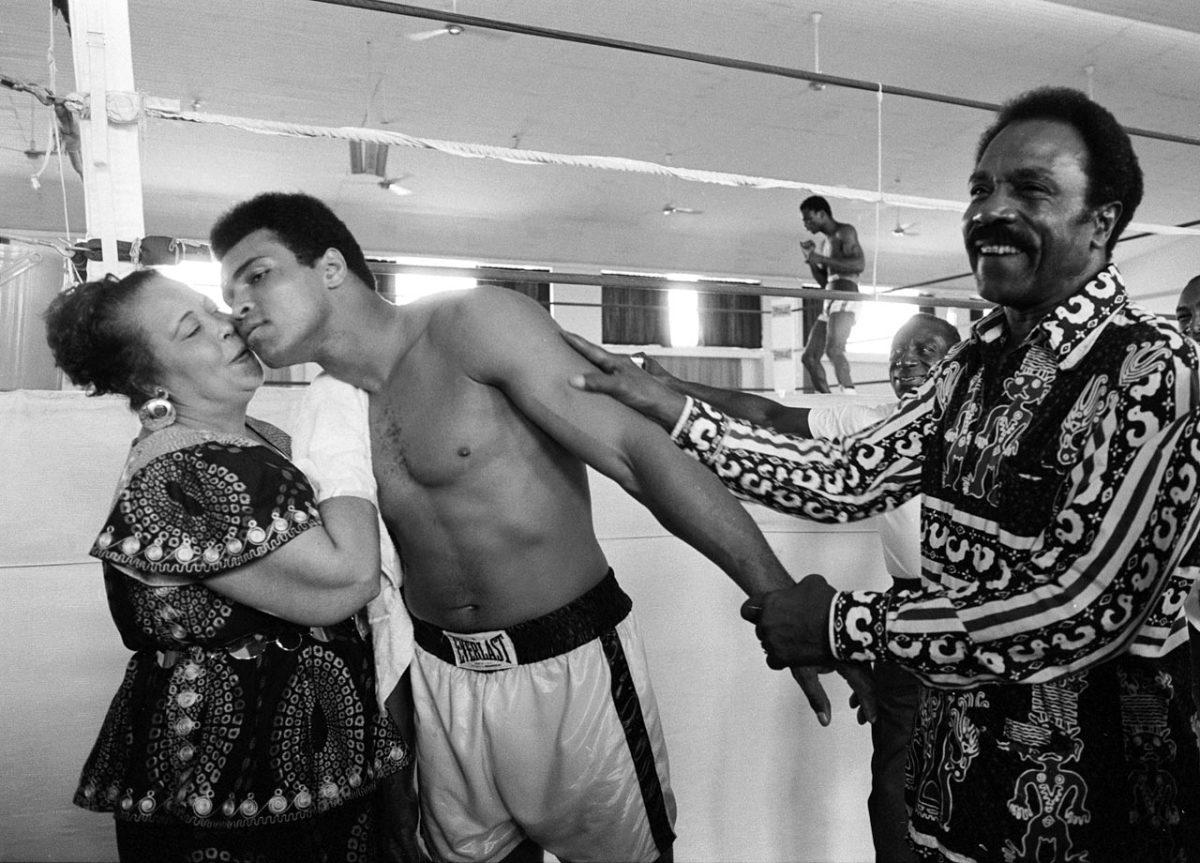

Image:

There can be no dramatic reprieve.

This is not the Rumble in the Jungle, where Ali defied all the predictions and chopped down a mighty oak tree called George Foreman.

This is not the Thrilla in Manila, the greatest heavyweight bout of all time, when Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier fought each other to the edge of death.

This is not boxing – the only sport that could never be described as a game.

It is terminal illness that Muhammad Ali is fighting, and for all of us it ends one way.

It is too soon to mourn Muhammad Ali.

But as he prepares for his final battle, locked inside the silent world of Parkinson’s disease, it is not too soon to remember what he’s meant to so many people.

In the 60s, a decade of supreme entertainers, Ali was the greatest of them all. He was a big man who moved like a dancer, a fighter who made the cruellest sport seem like an art.

In a racist world, Ali changed hearts and minds – forever.

Nobody could look at the young Muhammad Ali and ever again believe that black people were somehow inferior to white people.

Even when he was beating my family’s favourite domestic boxer, Henry Cooper, we did not stop loving him.

Even when he refused to go to the Vietnam War, and much of white America wanted him dead, we loved him in Britain.

My father – a working-class veteran of World War Two – might possibly have loathed Ali if we were from Baltimore rather than Billericay.

But in this country, we saw Ali’s sacrifice – the incredible courage it took to stand up to Uncle Sam, to risk serious jail time, to give up the very prime years of his sporting life for a principle.

He had the face of a film star and the heart of a lion.

Ali could be cruel – inside the ring, outside the ring, and in his personal life.

He sadistically beat up Floyd Patterson with the taunt: “What’s my name?” when Patterson insisted on calling him Cassius Clay.

He abused Joe Frazier with the kind of crude racism that he had helped to kill.

And as he was the greatest sex symbol of his time, he was inevitably never the most faithful of husbands.

Yet Ali changed lives as profoundly as Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela – and he did it with endless charisma, charm, good humour, a pretty face and a set of boxing skills that were indistinguishable from genius.

I was the perfect age to watch it all – from the fights against Sonny Liston, the clashes with our Henry, and the epic struggles with Foreman and Frazier.

Muhammad Ali was simply the greatest sportsman of my lifetime.

But Ali was – and is, and always will be – far more than a sportsman.

He proved that one man can change the world.

When I was growing up, I worshipped Muhammad Ali.

And as I read all the reports of a dying old man through a veil of tears, I realised a funny thing.

I still do.