Whoops!

Page not found!

The page you are trying to reach cannot be found. In the meantime feel free to search or check out the articles below.

Rangers Star Adam Fox Ripped In Comments By Players Around The League After Poor Four Nations Performance

Designer Vivien Agbakoba Accuses RHOP Star Stacey Rusch of Lying & Begging for Reunion Outfit She Originally Made for Ashley, Slams Her as “Phony”

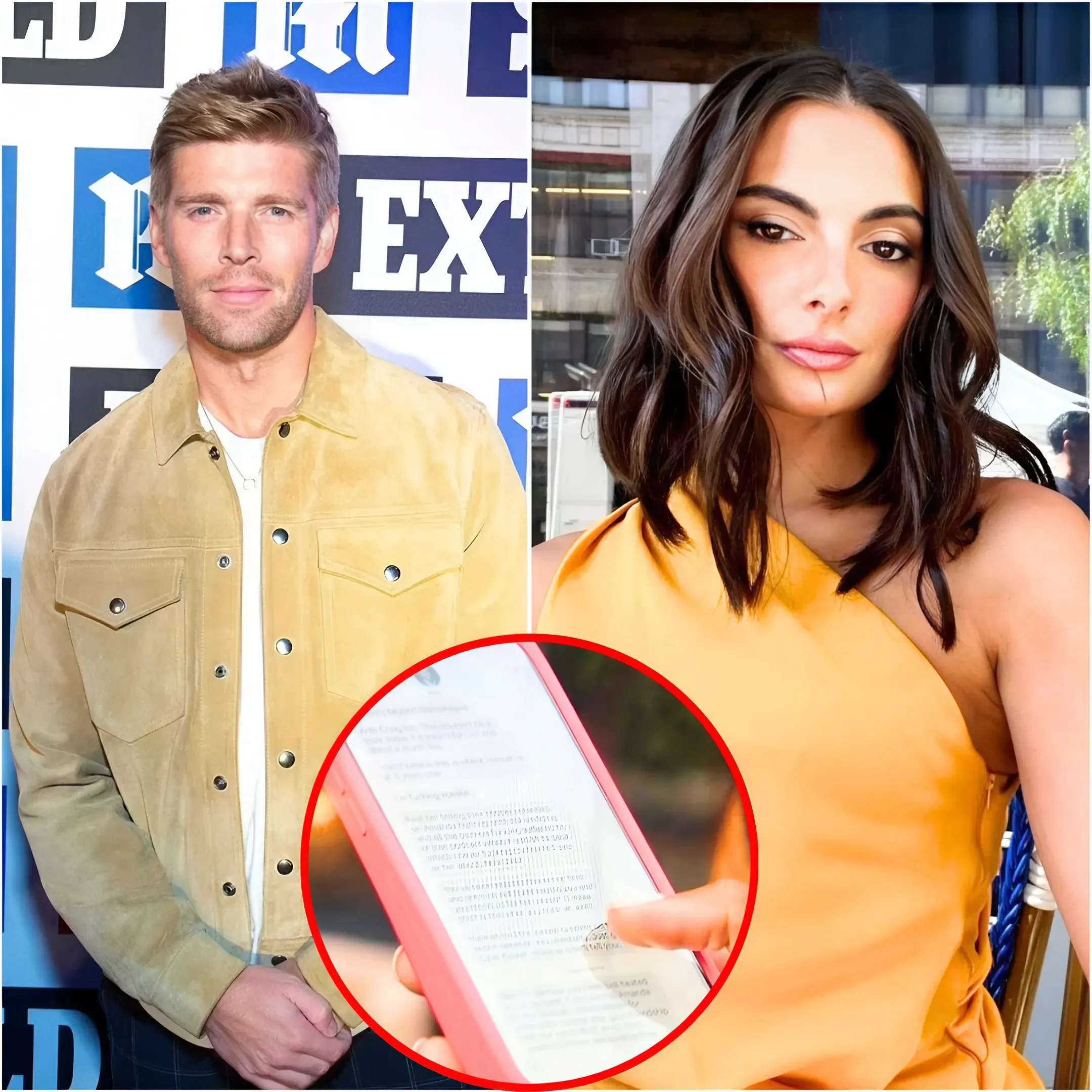

Summer House’s Kyle Cooke’s Rage Text to Paige DeSorbo is Leaked! See What He Allegedly Said About Craig and Hannah as He Admits Amanda Nearly “Divorced” Him

-1740470166-q80.webp)

The Bachelor: Grant's Rose Ceremony Is Halted When 1 Woman Asks to Pull Another Aside Moments Before His Decision (Exclusive)

-1740469626-q80.webp)