A version of this essay was originally published in the magazine Reconstruction in 1994 and is reprinted here with permission.

On Feb. 25, 1964, 22 years after his birth in Louisville, Kentucky, and a year before his rebirth as Muhammad Ali, Cassius Clay beat Sonny Liston to become the heavyweight champion of the boxing world. Clay got the title shot through victories that were few but impressive and an attention-attracting style. Clay did not win in silence. He won in a shower of lyrical self-praise and rhyming bravado. He told anyone who would listen that he was “the prettiest, the wittiest, and the greatest.”

At the end of the press conference following the Liston fight, only a few reporters remained when Clay spoke with a seriousness very different from his prior ballyhoo. Pressed to defend the separatist tenets of the Nation of Islam it was rumored he had embraced, the new heavyweight champion said the words that presaged his movement from the sports pages to the front pages. He said: “I don’t have to be what you want me to be.”

Although largely unreported, the statement is crucial because it predicts and explains Ali’s actions for the rest of the decade, actions often unpopular and enigmatic at the time: the announcement in 1964 of his decision to join Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, his declaration in 1966 that he was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, and his refusal in 1967 to be inducted into the U.S. Army on grounds that participation in war violated the tenets of his religion. The last action meant that for 3½ years Ali was forced to defend himself in court while being prohibited from defending his heavyweight boxing title in the ring.

However, it was not judges who kept Ali from prize fighting in the United States while his draft evasion case was litigated. It was boxing commissioners and politicians—sometimes on their own, sometimes under pressure from veterans’ groups, the press, and various self-appointed protectors of our “national honor.” The Ali ban was begun by Edwin Dooley, the president of the New York State Athletic Commission. During the afternoon of April 28, 1967, a few hours after Ali had formally refused induction but before he had been charged with a crime, Dooley announced that Ali’s license to box in New York had been “indefinitely suspended” because “his refusal to enter the service is regarded by the commission to be detrimental to the best interests of boxing.” Boxing commissions around the country quickly copied New York.

From the start, sports page condemnation of Ali’s stance on the war was almost universal. In Chicago, Tribune sports writers began the call for cancellation of Ali’s scheduled March 1966 title fight in the city. The cry was taken up on the editorial page, which wrote, “We find it deplorable that so many Chicagoans are unwittingly encouraging him by their interest in a fight whose profits go largely to the Black Muslims, upon whom Clay counts to rise up and save him from his duty to his country.” One week after the Tribune began its campaign, the fight was canceled. In May 1967, in a seething editorial, Sports Illustrated declared that “without his gloves on, Ali is just another demagogue and an apologist for his so-called religion, and his views on Vietnam don’t deserve rebuttal.” While the effect of such aspersions is hard to measure, the widely disseminated sports page criticisms helped justify the actions of elected and appointed officials that kept Ali out of the ring for so long. For example, many New York City newspaper writers supported the decision of the state’s athletic commission.

Ali did have a few defenders—Howard Cosell of ABC, Robert Lipsyte with the New York Times, and syndicated columnist Larry Merchant, among others. Indicative of their support was their willingness to refer to the fighter by the name he adopted in 1964: Muhammad Ali. The debate over his name may seem trivial. But it starkly symbolizes the potential problems and possible abuses fostered by an almost exclusively white fraternity of sports writers reporting and commenting on the actions and behavior of black athletes.

Banned from boxing, Ali pursued other activities to keep himself busy and solvent during his exile. He lectured on college campuses, published an autobiography in the “as told to …” genre, and starred in a Broadway musical. It was in exile, too, that Ali grew into a powerful symbol of black struggle. By late 1967, Ebony noted that Ali’s “popularity seems to have increased.” Although no pollsters recorded black sentiment toward Ali during his exile, expressions of support by leaders across the spectrum of black groups, and by blacks in public gatherings, and in articles and letters to black magazines, substantiate Ebony’s assertion.

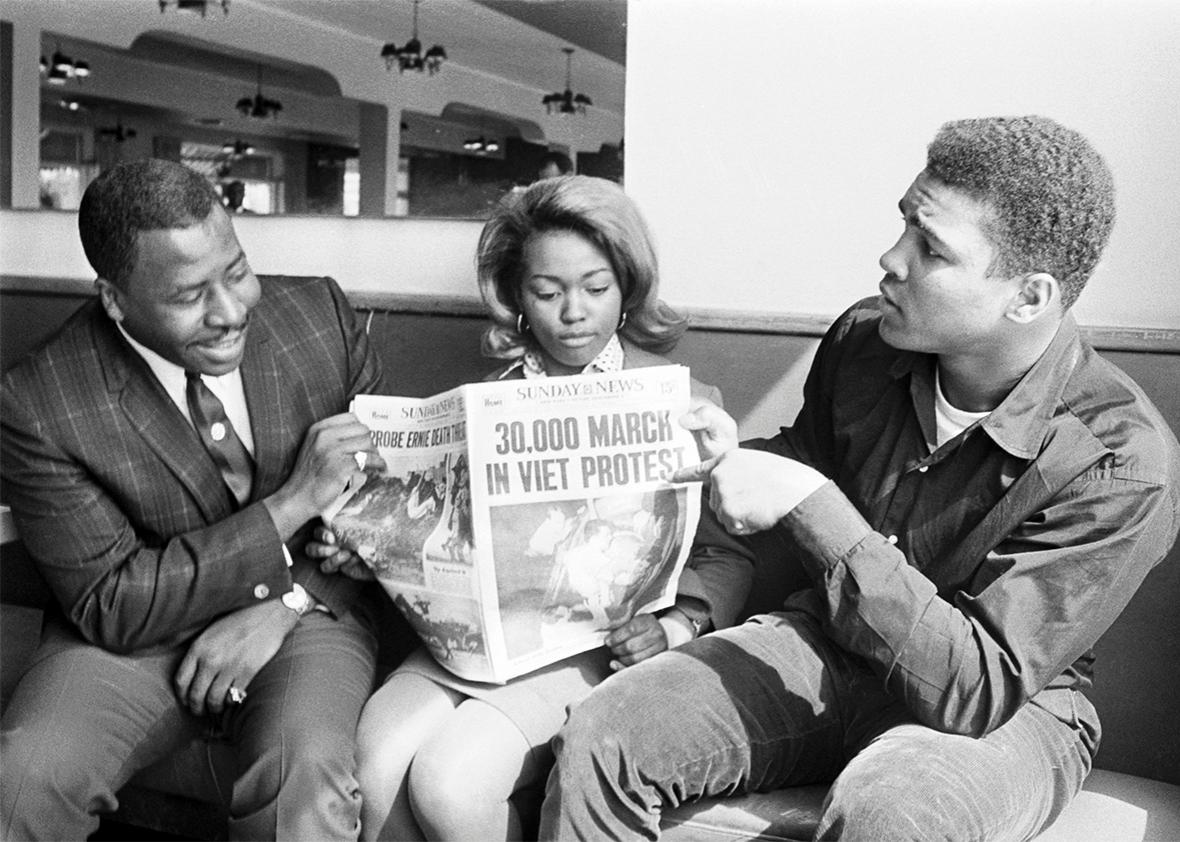

Why did support for Ali spread among black Americans? Part of the explanation can be found in blacks’ increasing dissatisfaction with the Vietnam War. Black opposition to the war emanated initially from the smaller, more militant groups—like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality —in conjunction with their advocacy of “Black Power.” Then, in 1967, came dissent from Martin Luther King Jr., who decided that peace in Vietnam and progress in civil rights were causes inextricably intertwined. King died before the killing stopped in Vietnam, but his year of opposition reached deep into the black community. He put a new perspective on the war, which probably led many to view Ali’s opposition in a new light. King repeatedly endorsed Ali’s refusal to fight. In speeches encouraging conscientious objectors, King told his audiences to “admire [Ali’s] courage. He is giving up fame. He is giving up millions of dollars to do what his conscience tells him is right.”

As increasing numbers of blacks developed an aversion to the Vietnam War, Ali began expressing his anti-war stance in a secular vocabulary that resonated with black Americans beyond the Nation of Islam. In court, he depended solely on his religious beliefs to justify his draft resistance. But in speeches and interviews during his exile, a dichotomy emerged in his reasons for opposing the war. “If I thought going to war would bring freedom, justice, and equality to the 22 million American Negroes in America,” Ali often said in the same interviews where he credited his Muslim belief with motivating his draft refusal, “they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow.”

Often his words were not original, but they helped to remove the perception of Ali as merely a Muslim minion reciting the group’s rhetoric like an automaton. The statements signified his emergence from under the Nation of Islam aegis and altered the lens through which blacks viewed the story of his resistance—no longer was it only Ali the member of a widely disdained religious sect defying the United States government. Rather, it was Ali the black man fighting for justice and fairness for all members of his race.

By the summer of 1968, while supporters, promoters, and his lawyers continued their efforts to find a city willing to allow Ali to fight, the appeal of his conviction for draft evasion had worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals had unanimously upheld the jury’s guilty verdict. The Supreme Court was under no obligation to review the 5th Circuit’s decision. And in late August, in one of the weekly conferences in which the justices decide which appeals will be heard, the court members voted not to hear an appeal in Clay v. United States. Ali’s legal battle had been lost. The conviction would stand. The sentence—a five-year prison term—would have to be served.

But then on Aug. 30, 1968, the Justice Department admitted that Ali had been overheard on telephone conversations with persons, including Martin Luther King, whom the FBI had been wiretapping. It was, as a then Supreme Court law clerk recalled, “like an act of God.”

On the basis of the revelation, the Supreme Court remanded Ali’s case to district court with instructions to determine whether the wiretaps were illegal and, if they were, whether the government had obtained evidence from the recordings that aided its case. Ali, for the moment, was kept out of prison. He was also still kept out of the ring.

In November 1969, Ali’s lawyers finally brought the question of his right to box into the judicial arena by filing a lawsuit against Edwin Dooley and the New York State Athletic Commission for revoking Ali’s license. His lawyers claimed that the commission arbitrarily punished their client “while on several occasions licens[ing] [other] professional boxers notwithstanding evidence that such individuals would be far more likely to be detrimental to the interests of boxing than the plaintiff.” The claim was initially rejected by the federal district judge for lack of evidence.

After the dismissal, Ali’s lawyers laboriously searched through New York State’s criminal records and found more than 200 instances of convicted felons being licensed by the NYSAC: men convicted of armed robbery, arson, rape, second-degree murder, and desertion from the Armed Forces had been allowed to box by the NYSAC. In light of the new evidence, Ali was granted a new hearing. This time the court ruled in his favor; Ali had regained the right to fight.

Simultaneous with the lawsuit against the NYSAC, supporters and promoters continued searching the country, supplicating cities and their officials to allow Ali to fight. Finally, in the least likely of places, a city was found willing to submit itself to media condemnations and politicians’ recriminations. Atlanta—in the middle of the South, in the domain of segregationist Gov. Lester Maddox—agreed to give an ostracized black boxer the opportunity to fight. The city’s liberal Jewish mayor withstood pressure from several sides and honored an agreement to let Ali fight Jerry Quarry in October 1970. At the time the deal was made between Ali and Atlanta, the outcome of his case against the NYSAC was still much in doubt. As it turned out, he won his case in September 1970. And, after a 42-month layoff, he won the fight in October.

For the moment, Ali was free to engage in the activity he excelled at without parallel. But he enjoyed a tenuous emancipation. Both the district court and the appellate court that reviewed Ali’s case on remand from the Supreme Court ruled that “the wiretaps were made in connection with persons other than the defendant [and] resulted in no prejudice and had no bearing on defendant’s conviction.” The case was appealed again to the Supreme Court and this time the justices agreed to hear it. On April 19, 1971, Chauncey Eskridge argued before the Supreme Court that Muhammad Ali was a legitimate conscientious objector, forbidden to fight by a religion in which he fervently believed. Two months later, the court declared a winner in Clay v. United States: a unanimous decision for Muhammad Ali.

* * *

Ali’s legal battles raise several important and troubling questions. One involves the role of the U.S. Department of Justice in Ali’s draft appeals and prosecution. In August 1966, the department convened a special hearing, appointing a former Kentucky State Circuit Court judge to preside, to determine the sincerity of Ali’s conscientious objector claim. The judge, Lawrence Grauman, listened to testimony from Ali, his parents, one of his attorneys, and a Muslim minister. He also received an FBI report on Ali. Because the Justice Department rarely overruled the decisions of the judges in these special hearings, Ali’s lawyers felt a favorable ruling was critical. A favorable ruling was what they got; Judge Grauman recommended that Ali’s conscientious objector claim be granted. The Department of Justice, however, ignored its judge. Instead it urged the state Draft Appeals Board to deny Ali conscientious objector status. The advice was followed.

The suspicious peculiarity of the Justice Department’s action is suggested by Carl Walker, the assistant U.S. attorney who presented the government’s case against Ali. As quoted in Thomas Hauser’s Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Walker observes:

I was responsible for prosecuting all of what we called the “draft evaders,” and this was the only case I know of where the hearing examiner recommended that conscientious objector status be given and it was turned down.

Walker adds, “I thought he should have been granted conscientious objector status all along, but that wasn’t a decision anyone in our office could make.”

Why did the DOJ decide to disregard the judge’s recommendation? Which Justice officials made the decision? What factors went into it? One possible influence was political pressure from congressmen like Mendel Rivers, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, who promised a Veterans of Foreign Wars convention that “we’re going to do something if that [draft] board takes your boy and leaves Clay home to double-talk.” There was another possible source of political pressure on the department to prosecute Ali: the president. Letters poured into the White House demanding that Ali be drafted. And once the prosecution of Ali began, the U.S. attorney handling the case, Morton Susman, was in contact with high-level White House officials. In one letter to Barefoot Sanders, a top aide to Lyndon Johnson, Susman reassured the White House that “this conviction will stick!”

Another issue that warrants more attention is why Ali’s lawyers waited so long—more than two years—to bring his right to fight suit against the New York State Athletic Commission. The attorneys’ hesitation cost their athlete-client irrecoverable time in his boxing prime.

* * *

Fame came first to Ali, the long visit beginning on that February night in Miami Beach in 1964 when only one of the two boxers fighting for the heavyweight championship rose from his stool for the seventh round. Almost simultaneously, he became important and controversial by converting to the Nation of Islam and resisting participation in the military. Now, he seems to be something different, something more—he is loved and venerated by blacks and whites. Why? In a doubt-filled world, it is comforting to see someone so pure in his devotion, so sure in his belief. Ali also seems to vindicate America. Although he surely could have, he refused to emigrate, instead submitting himself to the American legal system. And in the end, the system worked. Ali’s conviction was overturned. He was allowed to continue with his career.

But today it is clear that Ali’s 1971 vindication in the Supreme Court was, at most, an exceedingly narrow victory. Before Ali won in court, he lost a vast amount of a commodity whose value cannot be measured. For 3½ years, Ali was denied the opportunity to fight. Ali’s last fight of the 1960s came in March 1967. His opponent was Zora Folley. Ali was 25 years old. It was the ninth straight successful defense of his heavyweight title; his 29th victory in as many fights. When he fought again, he was 28.

Ali’s professional career divides naturally into halves. In the first half (1960–67), before he was banned from the ring, Ali avoided much of the physical punishment that boxers typically suffer. His head was an elusive target. His powerful hands deflected opponents’ punches. With few exceptions, the victories came quickly and easily. In the second half (1971–80), Ali had to fight ugly to win. Heavier and slower, no longer able to fatigue and frustrate his opponents by making them miss, Ali employed such tactics as the “rope-a-dope.” Leaning against the ropes, Ali would allow himself to be hit so often his opponents wearied from the opportunity. Then in the late rounds, he fought vigorously, hoping to knock out a now enervated foe. The victories were awesome—Ali beat Ken Norton, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, and then Frazier and Norton again. No other boxing streak compares; in all of sports maybe only Joe DiMaggio’s. But the physical and mental toll on Ali, as we know now, was just as dramatic. Ali’s Parkinson’s disease was caused, according to a medical expert in neurology who has treated Ali, by repeated blows to the head over time.

Other athletes have been denied opportunities to participate in professional sports at the peaks of their careers: the black men of the Negro League; those, like Ted Williams, who fought in war. But no other has suffered so much upon his return and for the remainder of his life. It is true Ali chose to get back in the ring; he was not forced to fight again, and again. What man, though, forced to forsake so great a gift for so long, could resist?

Ali must have realized during his exile, and after, what he was losing and what he had lost—those vital years from 25 to 28. For athletes in certain sports—basketball, baseball, boxing—these are the most productive years. Speed and strength have yet to be lost; experience has been gained. During those years Ali’s skills were dormant, his sinews went unused. As a man, Ali was free. But as a boxer—and that was the role that defined his life—Ali was incarcerated. Why did he continue fighting so long after his return? It was, I believe, an attempt to make up for the years he lost, and all the fights he would have won.